The Biden administration is riding a wave of rising optimism about the recovery from the COVID-19 recession, with the president and top surrogates hitting the road to sell their relief plan.

Economists say the U.S. is poised for rapid rebound thanks in part to the $1.9 trillion relief bill signed Thursday, which sends out another round of stimulus checks, extends expanded unemployment benefits and authorizes hundreds of billions of dollars in support for local governments, small businesses and hard-hit industries.

The White House is hoping to steer momentum from the bill’s passage behind President Biden’s other initiatives, such as a faster vaccination campaign, a package to rebuild the nation’s infrastructure and additional measures the administration and some economists consider essential for improving the long-run trajectory of the economy.

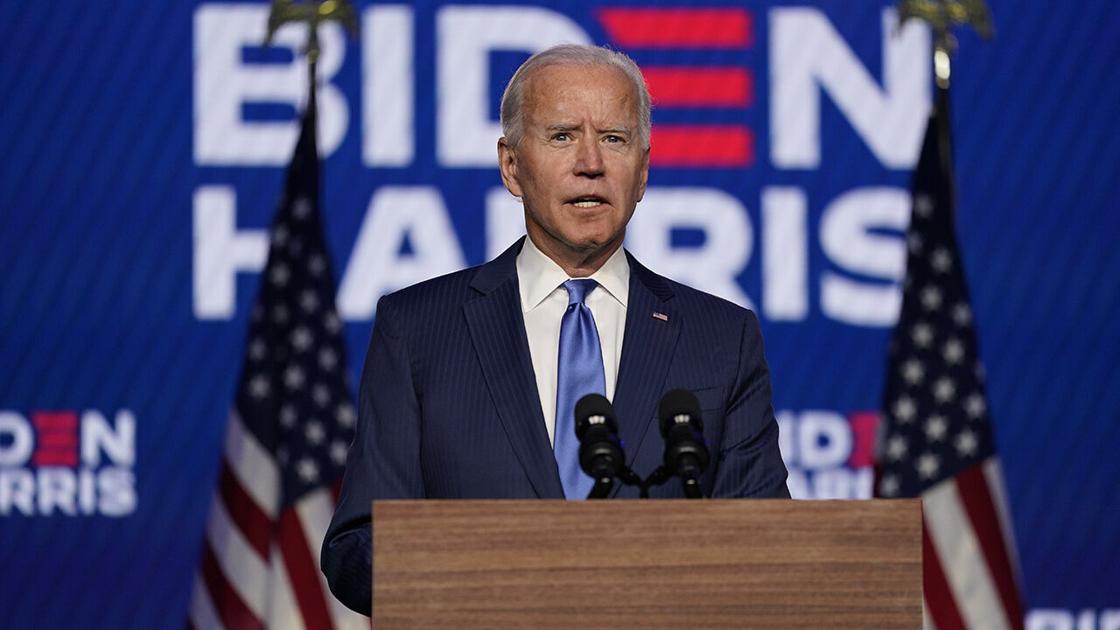

“After long, dark years—one whole year—there is light and hope of better days ahead if we all do our part,” Biden said during an address to the nation Thursday night. “This country will be vaccinated soon. Our economy will be on the mend, our kids will be back in school.”

“Over a year ago no one could have imagined what we were about to go through. But now we’re coming through it.”

Analysts are projecting gross domestic product (GDP) growth to between 5 and 7 percent in 2021, following a decline of 3.5 percent in 2020. The 6.2 percent unemployment rate, already much lower than its crisis peak of 14.7 percent, may fall below 4.1 percent by the end of the year, according to Goldman Sachs.

The new injection of aid also comes amid signs of a quickening economic rebound. The U.S. added a robust 379,000 jobs in February, consumer and corporate sentiment are soaring higher, jobless claims came in below expectations this week, and inflation has stayed well below the Federal Reserve’s target range of 2 percent.

The U.S. still has a steep climb ahead. Roughly 9.5 million jobs lost to COVID-19 have not yet been replaced, millions of households are still struggling through food and housing insecurity, and large swaths of the U.S. workforce will need to find new careers as entire industries attempt to rebuild from the ground up.

Even so, many economists are confident that Biden’s bill has kickstarted the process, with crucial lifelines to sinking families, help for states to fund essential services and ample support to last well beyond the direct payments to Americans that will be sent starting this weekend.

“The White House and Democrats on the Hill did an outstanding job in ensuring that the combination between immediate aid and additional aid…will combine with plentiful household savings to bolster the economy over the next three years at a minimum,” said Joe Brusuelas, chief economist at audit and tax firm RSM.

Biden is eager to show how he fulfilled his campaign promise to pass a major relief plan, which polling has shown is supported by roughly 75 percent of Americans. Biden is heading to key swing states to sell the package, which passed Congress without a single GOP vote.

The president will travel to Pennsylvania on Tuesday and hold an event in Atlanta with Vice President Harris on Friday. First lady Jill Biden will also hold an event in Concord, N.H., where Sen. Maggie Hassan (D) is expected to face a tough reelection campaign in 2022.

Republicans, however, say the huge rise in debt, potential for inflation and higher taxes will come back to haunt Biden — particularly as he attempts to pass a massive infrastructure bill.

“There’s not a country that sees this growth of debt and doesn’t end up with high interest rates and inflation,” Sen. Rick Scott (R-Fla.), a potential contender for the 2024 GOP presidential nomination, told The Hill.

“If you look at history, when you end up with an administration focused on raising taxes, you don’t end up with a growing economy. The only way out of this is to elect someone who knows how to grow the economy,” he said, brushing aside forecasts that the 2021 economy could grow at its fastest clip in nearly 40 years.

While both deficits and the debt soared under former President Trump, including $1.9 trillion in tax cuts and significant increases in domestic spending, Republicans railed against Biden’s $1.9 trillion rescue plan, saying it was poorly targeted and far too big.

They got some support from Larry Summers, who served as Treasury secretary under President Clinton and argued that the massive bill could overheat the economy.

With freshly-lined pockets, consumers would scramble for goods and services from businesses that remain short on capacity, leading to price increases and eventual interest rate rises, which could deflate the economy.

In the past, entrenched expectations that prices would keep rising kept borrowing costs high for homeowners, car owners and businesses alike.

Inflation concerns pushed bond yields to their highest point in a year on Friday.

But plenty of experts, including Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, have maintained that those fears are overblown.

“The economy is a long way from our employment and inflation goals, and it is likely to take some time for substantial further progress to be achieved,” Powell told the Senate Banking Committee last month.

He added that two decades of low inflation and a weaker relationship between government debt, low unemployment and price increases means the risks of overheating now are low.

February’s inflation figures came in at just 0.4 percent, and March’s consumer sentiment survey found that people are expecting only a temporary jump in prices.

Lindsey M. Piegza, chief economist at Stifel, says a little inflation won’t be the end of the world.

“With inflation averaging 1.3 percent over the past five years, there’s a potential for inflation to run near 3 percent for the next five without exceeding a longer-term average of 2 percent,” she said.

Scott, however, says Powell’s assessment misses the mark.

“He’s not looking at history. He’s clearly not looking at what’s happened in the past,” he said.

The debt may yet come to haunt Biden.

Even before the COVID-19 bill was signed, debt levels were already on track to surpass their World War II peak by the end of the decade. The cost of servicing the debt alone already amounts to some $300 billion a year, about 9 percent of annual revenues.

“Going forward, we need to start paying for new priorities with new revenue and budget savings. And ultimately, once the economy has recovered, we’re going to have to bring our deficits down to more sustainable levels,” said Maya MacGuineas, president of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

That could reduce the appetite for deficit-financed infrastructure from centrist Democrats and Republicans alike.

“They already maxed out the credit card. It’s going to make it very difficult for them to spend on things we care about,” Scott asserted, adding taxpayers don’t have the appetite for increased taxes.

Biden is still expected to press ahead on an infrastructure bill this year, and economists across the ideological spectrum have long considered those upgrades to be essential to accelerating the economy for years to come.

Brusuelas said without a significant infrastructure package, the U.S growth rate could slump back to its long-term trend of 1.8 percent per year.

“That is something that I would think, for most Americans, is not acceptable,” he said. “The stakes are enormously high here that we take advantage of what’s going to be several good years of growth, but follow through and leave a legacy.”

The Hill