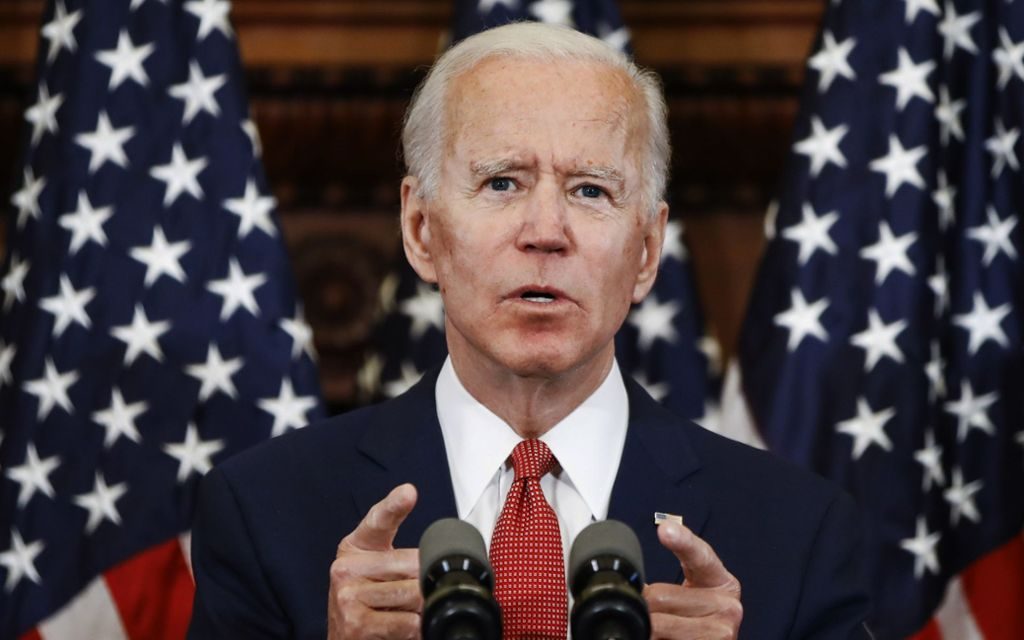

Joe Biden, who will take the oath of office on Wednesday as the 46th president in U.S. history, is vowing to succeed where his recent predecessors failed: uniting this fractured country.

Biden enters office at a perilous moment in history.

The nation is suffering through a worsening coronavirus epidemic that on Tuesday passed the grim milestone of 400,000 deaths.

A polarized political climate has been further damaged by conspiracy theories on social and traditional media, something that culminated in the ugly mob violence at the U.S. Capitol that interrupted the certification of Biden’s owl electoral victory.

An impeachment trial for President Trump threatens to interrupt Biden’s agenda, preventing him from moving forward with a cleaner slate.

Every president makes a commitment to bipartisanship, but few actually succeed in bringing the parties together.

Biden, who served in the Senate for more than three decades before becoming vice president, thinks he can defy history.

After his party’s wins in Georgia’s Senate runoff elections, Biden will at least have a Democratic House and Senate to help him.

But his majorities are razor-thin, creating a unique challenge for Biden.

Even with congressional majorities, Presidents Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Donald Trump ran into trouble.

Clinton’s stimulus plan in 1993 never got real traction and it was torpedoed by Republicans and centrist Democrats in the Senate.

Bush’s tax plan got off to a rocky start in his first 100 days and Trump couldn’t unify his party to repeal and replace ObamaCare.

President Obama, who had a huge House majority and a near 60-seat Senate majority at the beginning of his term, had more success out of the gate.

In his first weeks in office, Obama signed into law a large stimulus package, a pay equity measure and legislation that expanded children’s health insurance.

While many presidents have seen their approval ratings plummet after their first 100 days, Obama was not among them.

Obama’s approval rating was 65 percent at the conclusion of his first 100 days, the highest at that time since Reagan.

Biden will remember all of this, but he’ll also remember Obama’s legislation attracted minimal Republican support despite his popularity at the time.

Obama, who had run as a post partisan leader, became increasingly frustrated with the GOP. The partisanship only intensified as Democrats pivoted to climate change and the Affordable Care Act.

Biden is much more a creature of the Senate than Obama, who served just four years in the upper chamber before becoming president.

As Obama’s vice president, Biden was always the loyal soldier, but he privately indicated the White House’s relationship with congressional Republicans needed work. During a partisan fiscal showdown, Biden privately told then-Rep. Eric Cantor (R-Va.), “You know if I were doing this, I’d do it differently,” according to Bob Woodward’s book, “The Price of Politics.”

In a January 2009 meeting with congressional leaders, Obama brushed back Republicans amid a disagreement of what should be in his stimulus package, saying, “I won.” After he won reelection, Obama challenged Republicans to “go out and win an election.”

Ross Baker, a professor at Rutgers University and an expert on the presidency, said Biden is unlikely to be so pointed with congressional Republicans.

He added that Biden has an ability to break the tension in the room: “He is a good ice-breaker and enjoys working with lawmakers while Obama did not.”

That communication attribute could be an asset, especially when there is little warmth between Senate leaders Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) and Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.) and Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) and House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.).

Still, outside observers are skeptical.

“Long-term, I don’t think Biden really brings people together much,” said Keith Naughton, a Republican consultant who is an opinion contributor for The Hill.

“Too many differences and emotions. One thing that could help Biden is Trump fury at any members of Congress who he doesn’t think were loyal. Some may decide to retire (or have planned it anyway) and will be willing to make deals,” he added.

The first thing on Biden’s agenda is a $1.9 trillion COVID-19 relief package, and he’s expressed optimism that he can get Republicans on board. To pass a bill in the Senate, Democrats will need at least 10 Republicans to defect — which will be no easy task.

If Republicans block the bill, Democrats have said they would pass it with 51 votes using the budget reconciliation process. Yet, Democrats would first need to pass a budget resolution through the narrowly divided House and Senate. With a more comfortable majority, House Democrats failed to pass a budget in 2019 and 2020.

Throughout his campaign, there were questions about what kind of president Joe Biden wants to be. Washington will have a clearer idea after his first 100 days in office.

Republicans on the campaign trail accused him of being a “trojan horse” for a progressive agenda favored by Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.). Biden’s Cabinet picks, however, didn’t include Sanders or Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and many of his selections served in the Obama administration. Some on the left have grumbled about Biden’s early moves, most recently that he didn’t go bigger with his coronavirus plan.

Biden has appeased environmentalists by focusing on climate change and bringing in big names such as former Secretary of State John Kerry, ex-Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Gina McCarthy and former Michigan Gov. Jennifer Granholm (D) along with former Rep. Deb Haaland (D-N.M.) and 2020 presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg. The Sierra Club has called Biden’s nominations “an encouraging start.”

Climate activists are pushing the incoming administration to pass comprehensive clean energy legislation in 2021 and climate change has long been Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s (D-Calif.) signature issue. While getting such a bill through Congress faces an uphill battle, Biden can tackle some aspects of climate change through executive orders and regulations.

In retrospect, some Republicans wished Trump had made transportation, not health care, his first legislative priority. Trying to eradicate the Affordable Care Act right out of the gate made both parties dig in for what was an intense partisan battle. At times, talks on transportation picked up, but the administration never made a concerted, consistent effort to pass a massive bill.

Biden has also vowed to push for legislation on infrastructure, which has traditionally attracted bipartisan support. It remains unclear if Biden will make this one of his top priorities in his first 100 days. Some Democrats see infrastructure legislation as intertwined with climate protections and an emphasis on the latter could erode GOP support.

The biggest obstacle to a sweeping transportation/infrastructure bill is how to pay for it amid record debt levels. There has been speculation that Biden could make the case not to pay for it in the near term amid the coronavirus pandemic.

Biden campaigned on repealing parts of Trump’s tax law and increasing taxes on corporations and wealthy people. However, it’s unlikely Biden will seek to raise taxes in the foreseeable future. To do so, an overwhelming majority of Democrats in the House and likely all Democrats in the Senate would have to get behind such a plan. Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.), a centrist who will hold a lot of power in the 50-50 Senate, has previously said he doesn’t favor raising taxes during economic downturns. Manchin, who voted against Trump’s tax bill, has not indicated whether he favors moving forward on Biden’s tax plan.

Democratic congressional leaders and Biden are expected to have a smoother relationship than in the Obama era. Exasperated with Republican lawmakers being “a rubber stamp” for Bush, Democrats made clear to the Obama White House that they were going to have a lot of input on the congressional agenda.

Soon before Obama was sworn in, then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) said, “I don’t work for Obama.”

At around the same time, House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer (D-Md.) told reporters, “I don’t think the White House has the ability to tell us what to do.”

After four years of Trump, there is little daylight — so far — between Biden and key congressional Democrats.

Biden, who has known Pelosi and Schumer for decades, has deferred to Congress on how and when it will proceed with an impeachment trial on Trump. Still, Biden and his team are anxious to govern.

No final decisions on the timing of a trial have been made, though Democrats across the board know they cannot pursue a lengthy trial of Trump while wasting Biden’s political capital and ignoring calls for coronavirus relief.

Baker said Biden’s goal is not to win over most of the 74 million plus people who voted for Trump. That is not feasible, especially since 7 in 10 Republicans say Biden was not legitimately elected, according to a recent Washington Post-ABC News poll.

The Hill